I submitted this to the Lamp magazine; the silent response suggests it’s not in their wheelhouse. If anyone’s interested in syndicating this piece, though, let me know. I might be able to augment it with interviews of the band members.

Wer kennt eigentlich die Bedlam Rovers; hat tatsächlich schon einmal ihre Musik gehört? “Who actually knows of the Bedlam Rovers, or has heard their music before?” asks one of their interviewers. Enough people have heard of them, it seems, that Alternative Tentacles dropped their name in a band description, and they have an entry in Pietro Scaruffi’s (who?) archive of obscure rock bands; so they have, or had, some relevance.

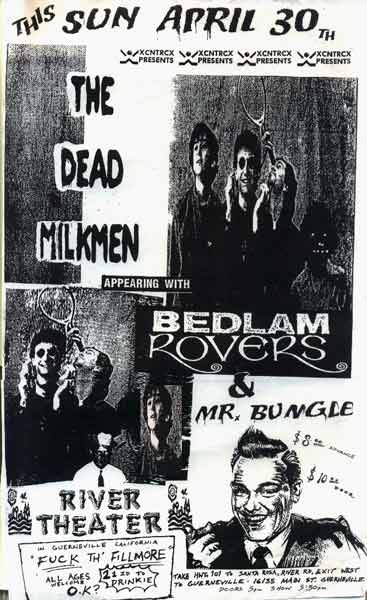

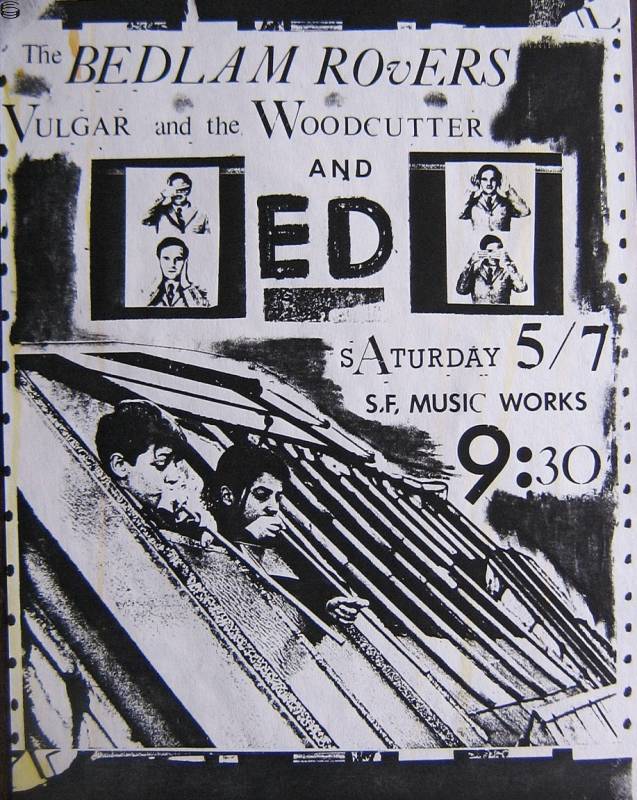

At first glance their name seems like another silly indie-rock nonce, the coupling of two words that mean nothing together; but separated, “Bedlam” and “Rovers” begin to ring bells, because both are common tropes in Irish-music band names. (Think “the Bedlam Boys” and “the Irish Rovers.”) The Bedlam Rovers started thus, playing “sham-rock” in San Francisco at the “semi-legal” Club Komotion run by members of the band; former D.C. punk ”Li’l Mike” Martzke has uploaded a few YouTube clips from this period, when he sang for them. At this point their ethos came from brothers Andrew (drums) and Jeremy Doyle (mandolin, bouzouki), who briefly gaelicized their name to “O’Doughaill” as part of the bit. In this period they recorded a riff on Black Flag’s “Rise Above,” recognizable only from the title and from snatches of its music, and a few songs for local compilations.

By the time of their Frothing Green album the Rovers were starting to move away from the Irish style, and guitar player Marko Sakmann started writing anarchist-pastoral lyrics for the music the band was jamming on. One of the best of these is the “Bizness Suit Hoedown,” the story of a group of former tenants who take over their gentrifying apartment building, and squat there to the discomfiture of the “upgrad[ing]” landlord. Sakmann also predicted that “if the rents keep goin’ up… much higher” in San Francisco, “we’ll be livin’ in the street, keepin’ warm by a fire.” One thinks grimly that this was more than rhetoric.

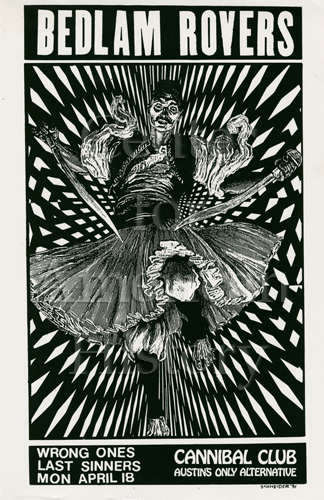

In spite of its first-album shortcomings (prolix lyrics, some bland music, rhythms that don’t exactly rock), Frothing Green has a utopian charm that their other albums would mostly lack. The Rovers had a cynical, even nasty streak from the beginning, expressed in their un-patriotic “XTC Waltz,” and that cynicism came to the front on Wallow in 1992, after Jeremy O’Doughaill left. His brother Andrew stayed to play drums on the next album, but Jeremy seems to have taken with him the band’s stock of traditional melodies and willingness to continue playing old Irish music. A Boston concert taped by Francis “The Wrong Hero” DiMenno features only one traditional song, “Home Be Bearna,” which appeared on Frothing Green — most of the show is comprised of new songs from Wallow (which featured only one Irish song, “Hot Asphalt”) and a couple that would show up on the equally ingrown Land of No Surprises.

With their second record, Wallow, the Rovers’ music became as alienated as their lyrics. Clunky dissonances give away the guiding hand of a guitar player, in “Heaven Song” and “Count to 20” and “Eat My Pie.” Some of the lyrical targets are the usual objects of feminist-progressive hang-ups — Columbus, General Custer (twice), the Marlboro Man, G.I. Joe — but many others indicate an engaged, historically literate, and thoughtful leftism. At the end of “Big Drill,” over one of the mightiest I-IV vamps you’ve never gehört, Caroleen Beatty blasts the atom-bomb project at Los Alamos and the prospect of mining Antarctica. (Marko Sakmann takes an admirably hard line against the Bomb, in “Big Drill,” “Nevada,” and the next album’s “Flat,” a song about the crew of John Wayne’s last film catching the fallout of a nuclear test in New Mexico.) Marko also turns in complaints about performative liberal activism and crunchy Californian lifestyle politics, and an accidental refutation of materialist anthropology:

I have books and time to spend

And I have a soul and I have friends

And I have a home and I have food

And still I have a bad fucking attitude

And the cynicism and political orientation aren’t total even on Wallow: they give way briefly to a beautiful, childish reverie in “Nevada”:

On the map there’s a big gray square

They said don’t worry, there’s no water down there

And I have a friend who talks to the trees

He says he’s never seen trees on their knees

The song is an anti-nuke protest, so obscure that its meaning is impossible to detect without the liner notes of the Don’t Forget! single; but what red-blooded American could hear about a big square on a map and not feel again his childhood yearning for the Platonic tan canvas of the Mojave, for the verdant banks of the Colorado River, for a drive up Going-To-The-Sun Road between ten-foot walls of plowed snow, and all the other wonders of the “incredible shrinking West” (one of Marko’s priceless coinages, from “Bob the Mechanic“)? “Nevada’s” equivalent on Land of No Surprises is the sympathetic “Kerosene” (not the Steve Albini song), a ballad in which “on angel’s wings” a poor, abandoned Middle American drunk “rises/To dance another jig/In the land of no surprises.” And its proxy on Frothing Green is the title song, where Marko lays out the difficulties in building a moral present on the foundation of a corrupt past. Though the Rovers find little worth venerating in history, the struggles of human beings past and present earn their respect — also very American.

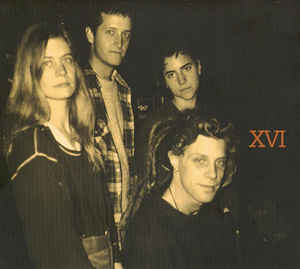

Bob Christgau once said that the American musician is always “closer to down-home funk than his… English counterpart.” Accordingly, the Bedlam Rovers’ American-communitarian ensemble sound, like the best county-fair band that never was, makes them much better rockers than the Mekons and other British post-punk groups they get compared to. And their sense of humor makes them much more fun to listen to than the undergraduate despair of the Gang of Four. They never fully developed a sonic signature like, say, the Cows, but one is thankful that they found such good fiddle players — the countermelodies played by Cindy Wiggington, Shannon “Squeaky” McGuire, and Morgan Fichter enliven songs that would’ve otherwise seemed a little wooden. (I say with all affection that Marko Sakmann has one of the worst guitar tones I’ve ever heard.)

Given their traditional and historical engagements, it’s tempting to say that the Rovers make “old weird American” music, to use a term coined by Greil Marcus to describe the Basement Tapes’ connection to prewar American folk music and culture. Tom Waits, with all his faults and accomplishments taken together, is arguably our most famous monger of the “old weird America” concept; Neil Young and John Prine sometimes trade on its tropes. Other roots-impressionist indie-rock groups, like the Walkabouts or Genghis Angus or the Little Saints, fit the bill. But what I found attractive about the Bedlam Rovers, when I first heard their Roll Over EP in July 2019, was that their tough-minded music matched their status as activists instead of aesthetes, rarely bourgeois enough to pine for a place where the circus never ends. In that German interview the bassist, Greg Snyder, rejects the prospect of abolishing work, saying that “every society needs a structure in which people work for common cause. You have to work to live.” At their best they bring to mind instead that ultra-American folk communist Woody Guthrie, whose sharp political instincts were grounded in humane outrage at injustice and joy in human potential. Guthrie’s liberal, social-gospel Christianity and moral optimism, the original planting soil of communism, have been mostly (inevitably?) abandoned by later American leftists; they were slowly replaced by the rage and pessimism which characterize the Bedlam Rovers’ later music. But little bits of that grounding love show through all the time, in the (probably) unironic praise of country life in “Laughin’ Babies and Sneezin’ Dogs,” in the acedia of “Difference” and “Emily” and John Prine’s “Angel From Montgomery,” in the demands for dignity on “No One’s Illegal” and “Bizness Suit Hoedown” and their rave-up on Billy Bragg’s “To Have and to Have Not.”

Their take on religion is pretty bog-standard. At the Boston concert they introduce their own “Peace Train” as a song that “calls for the death of Cat Stevens,” alluding to a tabloid-baiting comment which the newly minted Yusuf Islam later retracted. And in “Count to 20” they inform a “cowboy” that “not all the Indians have… repented of their sins,” as though pious hypocrisy were the besetting sin of Dodge and Virginia Cities. But the protagonist of “Emily,” one of my favorite Rovers songs, kneels down to pray at the end of her song. It’s unclear whether she perseveres, when the lyric says “Never believe in divine saving/A last resort, a chocolate craving”: is she saying this to herself, or is the narrator scoffing for her? Either way, the Rovers’ humanism and love of justice gives Christians like me reason to hope: that saying that “if you’re not mad, you’re not paying attention,” is almost as true of faith as of politics. And your correspondent, who was not always a Christian, recalls that he did some of his scoffiest scoffing just as his own knees were beginning to bend.