Three Russian albums figure prominently in my music collection. The first I found was Valery Gergiev and the Kirov Orchestra’s version of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. While I have not listened to many other recordings of that famous piece, I can say without reservation that the Gergiev version rises head and shoulders above the ones I have, stupendously portraying what Stravinsky himself called the “earth cracking open and groaning.” The second, Air Canda, is the self-nominative debut of a jazzy progressive-rock band with a strong dedication to the brainy avant-garde but also to the propositions of rock and funk. They are the reason I took notice of R.A.I.G. Records, the label on which Disen Gage were also based for awhile.

This album, as you may have guessed by now, is the third. It was my second R.A.I.G. purchase. I was drawn in by its cover art, with the birdcage-headed man and all; it was supposed to be trippy, but was just absurd enough to get a chuckle out of a cultured listener. After all, that’s what I was. *Elicits a bored “pffft” from the crowd*

Since I was browsing the catalog on Bandcamp, I was able to listen to the music beforehand. I focused my beams on the first two pieces, “What’s Up on Planet Plyuk?” and “Landing (including “Mamushka”),” and attempted entry.

Disclaimer: “Planet Plyuk” is a track to avoid for anyone who dislikes the polka. Its hilarious intro includes the sound of water moving through pipes behind a cheap plywood wall, as though the listener were crammed into some European-size apartment. The music begins. The reverb is cold and relatively narrow, but spacious on the top, cloudy but not gloomy. It is morning music for Western Russia, the soundtrack over which one wakes up and asks: “Shit, what am I going to do today?”

As the song develops, the nerdy little lead guitar (this is, after all, a band of biochemistry Ph.D.’s) takes charge and speaks with more eloquence, repeating himself for effect occasionally and suddenly, with the band’s entry, drops into a lower register to address us in friendly song. The band behind him is hard-hitting and swaggers through — hey, that’s a rock beat behind our friend, and a horn section. What kind of goofy crap is this? I came for the oompah, and I leave with a parade march.

Give the bass a few measures to himself, as he boinks along in 5/4 with some lowercase electronic beeps and boops, and then the rest of the instruments take over the song again. Suddenly it’s a fast 4/4 gunslinger, with the original guitar right out in front of the hollow trebly drums, the bass pining beneath it; the guitar cries a few more notes from the original theme, before the tape loops backwards in the machine for two bars and the guitar drops back in again without missing a beat; he exits and the song’s brakes kick in soon enough. As the band finally drops out, the plumbing noise returns momentarily, only to exit as well with a grand spacious whoosh. A building wave of cymbals crests over the next song, and a series of dissonant major thirds introduces “Landing.”

There is very little else one can say about “Landing,” except that it’s a crying shame that it includes no spy-chase music video. It starts with laid-back intrigue, rises to an insistent thrust; adopts a secretive industrial tone, returns to spy music; erupts into hideous metallic laughter, and swings back and forth like a maniac to the screams of synthesized horns; has a moment of clarity and beauty; returns to brilliant mechanized instability. Another piece of quietude attempts to clarify the situation — this must be the nightclub scene. Instead it only makes things foggier and more incomprehensible. The pursuer steps outside to clear his head, sees his target. Their pulses rise in unison, until the one is chasing the other through the streets of Berlin or Moscow or some such sophisticated city, stealing mopeds left and right, flailing desperately through the eight-inch avenues, crossing thousand-year-old bridges, but each equally matched (the music changes chords slightly to indicate whose point of view is whose) until the triumphant hero comes close, and then I guess both find a tank to drive like in that Pierce Brosnan-as-James Bond movie. All hell breaks loose to the pounding doop-chick beat, with little interludes for the band members to shout “Mamushka” at increasing volumes, trading fours with their own instruments to heighten the manic-schizophrenic minisym. Then a tragic denouement, ending the song on a minor chord when a major should have triumphed — the bad guy wins, I guess. Shit happens.

Next is “Lehaim to N.E.P.” I used to think that it was a tribute to some kind of futuristic train route, like “Trans-Europe Express,” but I googled “Lehaim” and “N.E.P.” separately and learned that the former is a Jewish blessing (along the lines of “to life” or “long live X”) and the latter the acronym for Lenin’s pro-capitalistic New Economic Plan. In other words, the title actually means “long live pro-capitalistic Soviet policy.” Go figure. The song itself is as nonsensical as its title, bursting into flowering trumpet solos and snaking along the most dumb-hilarious melodic lines this side of Frank Zappa. A couple of guitar solos serve to raise the song’s profile more than a little. It ends on exactly the wrong chord after an irregular number of bars, just to mess with us.

“Exyrinx” begins with a solemn solo guitar lead, issued from high on a windswept ridge in the steppes of the barren East. Bass and drums work in tandem, pursuing mind-bending goofy textures in the pursuit of irony. Over this does the guitar progress, dropping into its cavernous low register and appearing in the right speaker and the high and low center of the aural space. It grows more distinct and trebly over time, as electronic whicks and whocks build in the background (god, this producer is brilliant) until the bass adopts a different rhythm and guitar 2 enters; a short, anxious new theme enters and drops out again in favor of the old jam, but returns and moves forward (jumping out occasionally to a new piece) and perverting the original beat once more before returning to the height of tension, a paranoid guitar wailing in the foreground and balling up again before the release of a flood of tension and the return to a more insistent variation on the original lead. The bass and drums repeat their earlier loop and a gentle tremulous organ washes the surrounding soundscape clean, like a mother and her bubble-bath soap. The guitar becomes sentimental once again and winds the piece down again to a crackling lo-fie background.

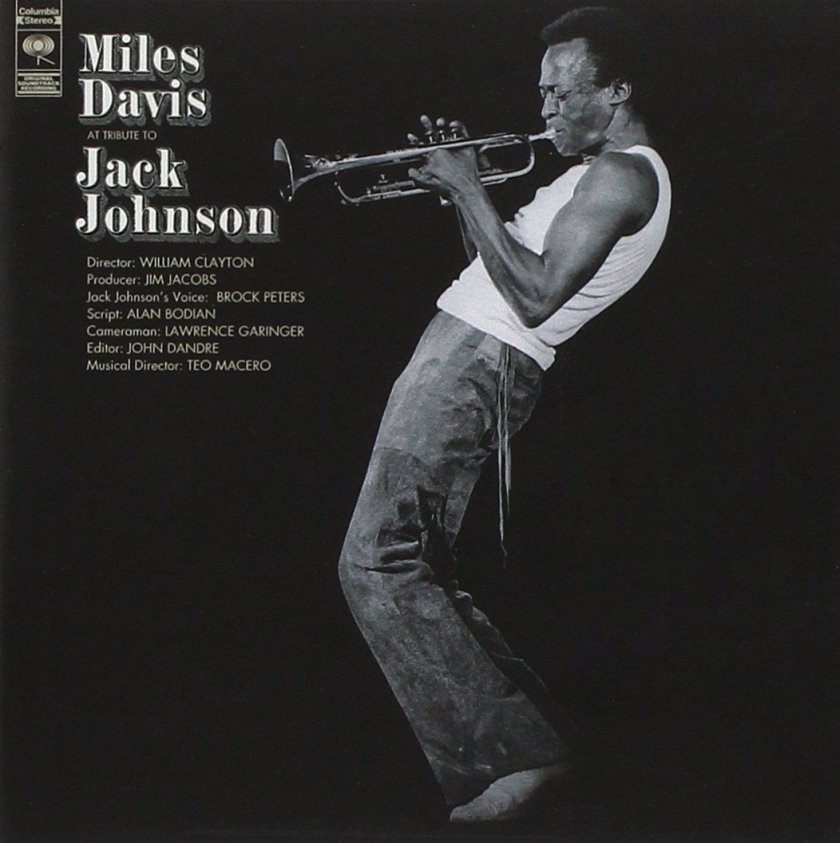

“To Kill Kenny” is not the best track here, but leaves no doubts about the band’s love of arpeggios. I do not complain — I love innovative ones myself, and when the rhythmic guitar on the left begins to interact with the right it becomes pure bliss. The song adopts a pleading tone partway through, but leads eventually to a speedening crescendo and several key changes to ultimately… sort of… pass away. The last chord in the song is major when it should be minor. (I already used the term “Picardy third” in my Jack Johnson review, so I will demur here.)

Say, isn’t that Les Claypool? “The Parovoz Hitchhikers to Japan” (if you can’t tell, the concept is related to the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series, which I absolutely adore) begins with a slap-bass riff, and the guitar moves in predatorily to play some surprisingly pentatonic licks: key one, semitone higher, octave jump, octave and semitone, before reverting and skipping back down the neck with this epic flourish (hear and believe!) before rolling under again and then returning to the original riff. The epic lick is repeated, and the return to subtlety; then another factory-made quasi-rhythmic clang, until crowds of people materialize in the background, and steel drums — of all the hilariously tasteless instruments to insert — play a brief solo. A halting boink grows in intensity until a guitar screams behind it, begging the audience for reprieve before it finally goes the “artistic” route and commits suicide, and a blistering return from the first motif only once, before the song fades out on a single synthesizer chord.

This was originally my favorite track.

“God Saw Otherwise,” if I may appropriate mental-health imagery for a second, begins with a bad case of Tourette’s Syndrome, interrupting its timid guitar lines with explosive bassy thumps every few measures. Each chorus (the structure is almost conventional, when compared to the likes of “Landing” and “Exyrinx”) lets loose with heavyweight thuds, and a decent enough bridge makes it a good song, if not epic. It passes out in about three minutes from lack of oxygen.

“Laxatives Are Included” constitutes a return to form, however. A sluggish bassline introduces the song, until the guitar and drums give it a sense of more regimented laziness: a drowsy platoon on parade. Throughout, a Blixa Bargeld-ish sheen of slide feedback shimmers and squiggles comically. The song dunders along quite hilariously for a few minutes, until it goes back to straight 4/4 and begins a devious series of variations on the original theme; the song, ridden with anxiety, picks up the the pace gradually, reaches a reverbed climax, then reverts to a momentary attempt to find the fret the guitarists were playing earlier. The original theme is stated, and the bass slides into the midrange to give us the final note. The shiny ambient Blixa guitar fades.

We then get “Ikar’s Guide to the Galaxy.” (Get it? Like “Hiker’s,” but different? We’re so funny, Disen Gage and I.) This is the other “epic” song present. The opening motif reminds me a lot of Irish music, with the pentatonic jig and all that, but the band is never less than eager to jerk you around, and quickly winds things down into palm-muted territory, where under the guitars we can hear a synthesizer and somebody making cute mouth noises. The speaker begins to shout “Lyuli-Potzelui” (apparently means “gypsy kisses” in Uzbek or something) in a ridiculous falsetto. They will do it again. A few more bars, and then a short burst of incendiary ’80’s metal guitar, then a muted vibraphone solo. Seriously.

More mechanical beats and atonal guitar abuse. These chugging riffs raise the stakes until we’re at an entirely new level, and then the breaks begins: cracks in the foundation, band members screaming the words from the song’s title (which appears to mean “gypsy kisses,” but I don’t speak Uzbek so it’s uncertain) for a few bars, trading off with the guitars like in “Landing” until the song just… disappears. In its place is a French voice and some cool-jazzy bass ambience, which is replaced soon enough by a spacious, melodramatic piece that could have come from a 20th-century symphony or a semi-lame jazz fusion album. Not that it’s bad — just a little over-the-top. Kind of like the rest of the album. But hey, it comes with the territory when you’re the best ironic prog band in Russia.

A couple of peeping sounds introduce “How Much Is Oxygen On Planet Khanud?” and a bassline follows them. It swings along for a couple of minutes, but eventually slides into that big, dramatic atmosphere from the end of the previous song. This one is a bit more fleshed out, and features what sounds almost like a bass solo with both noisy and wahed guitars; the first motif, now absent the swing, plays once more. The tempo picks up, doing that half-step-at-a-time I love so much in Guru Guru and jazzy music, but unfortunately the piece dissipates in time and the album comes to a regrettable end. A man shouts in Russian as the peeps come back and the toilet sound from track 1 is reprised, and that’s the end of …the reverse may be true.

A final note (DO NOT READ UNTIL YOU HAVE HEARD THE RECORDING): according to the Bandcamp liner notes, the album was recorded solely with the use of guitars and effects pedals. That means all the instruments you heard — brass section, trumpet, steel drums, harmonium, peep-whistle (whatever played the intro to “Planet Khanud”), vibes, synthesizer, flute, calliope, theremin and anything else I missed — are special effects played on some dude’s guitar. Each solo, it seems, was played in the style of the instrument it emulated, and quite well done too. I think it might be Sergei Bagin who brings these pedals to the table — they aren’t in evidence on The Screw-Loose Entertainment, the album recorded before he joined the band, but they are definitely in the fabric of its descendant Libertage. You’ve probably stopped reading by now, so let me reiterate:

DISEN GAGE = GOOD. REVERSE IS BEST DISEN GAGE ALBUM. GO NOW. TUNE IN.

My opinion of this album continues to rise.